My tongue has always been my biggest sensory of confusion, it is why learning Spanish was a necessary transition from my colonizing split between English and Arabic, mi propia existencia “rajada” (Anzaldua). What can our presence create in between our ancestors’ walkways of history and the current political time? Anzaldua describes in her book, Borderlands, that these points of crossing, meeting, protecting, and identifying the borders of colonialism are all embodied in our daily performances. Anzaldua demonstrates how understanding this intra-movement and hybridity in our performance is necessary in the battle to individually, but as a racial entity, voice the needs of colonized populations and lands.

“our psyches resemble the bordertowns and are populated by the same people. The struggle has always been inner, and is pIayed out in the outer terrains. Awareness of our situation must come before inner changes, which in turn come before changes in society. Nothing happens in the “real” world unless it first happens in the images in our heads.” (Anzaldua, 87)

How do we find our true faces, asks Anzaldua, a question I place in response to Paz’ writing in Mexican Masks. Como se piensa, en primero, y despues como se actua las fronteras in la lengua del colonialismo global, en mi lengua personal? My tongue is my language. My language is my presence. My presence is my solidarity and purpose. How do I declare my presence? How do I say “Present/e” in my father’s tribal dialect, my french-colonized mother-tongue, in modern standard Arabic? In the Black English I inherited from living in Black America and listening to Black American music? In the academic English and Spanish literature I was trained in through my scholarship in the American University? In the Boricua Spanish I have been welcomed into understanding? These are the “states of betweenness” Taylor argues need to be discussed in order to truly begin to formulate and fight for the heterogenous we that being “present/e” strives for (Taylor 8). Is a declaration of self even necessary? Am I anything alone? What is this “I” of presence even an assemblage of? Is the “I” not merely a reflection of everything you are in contact with and what you experience? Can I walk with others with dignity, respect, patient listening, witnessing and solidarity? These are the immediate arguments Diana Taylor’s introduction, ¡Presente!, brings to my mind from her critically concise writing. Above, I pose my own questions as critically-thinking explanations of Diana Taylor’s arguments: albeit having understood them personally through my own experiences and academic understanding of the violent global erasures and epistemologies of colonized history. Taylor’s arguments in ¡Presente! are yet still fixed both in individual self-reflection (how are you present? in what energetic way do you do everything?) but also in direct relation to life as a “walking with others” (Taylor). Taylor’s main argument in her essay clearly negates the need to circulate knowledge around the I: “¡presente! as protest, as witnessing, as solidarity, as being in place and with others.” (Taylor 7). Taylor is describing how this walk with others is a self-decolonizing act of the individualistic mind founded on inherently abusive power orders of colonialism and violent erasures of indigenous identity. Is the contradiction of being “present/e” being the “Nobody” Paz introduces to us in his conclusion? Are the masks of mimicry that Octavio Paz argues in his chapter, Mexican Masks, what we need to take off in order to walk with the force of being Presente!? Paz describes that colonized individuals dissimulate themselves into the colonizer’s environment that they are forced into, becoming invisible subjects. Paz situates this in the example of Mexico’s history, but I argue that this is also a global argument on colonization. The Global South dissimulates in reaction to Northern, Western, Occidental power structures.

Our dissimulation here is a great deal more radical: we change him from somebody into nobody, into nothingness. And this nothingness takes on its own individuality, with a recognizable face and figure, and suddenly becomes Nobody. (Paz, 45)

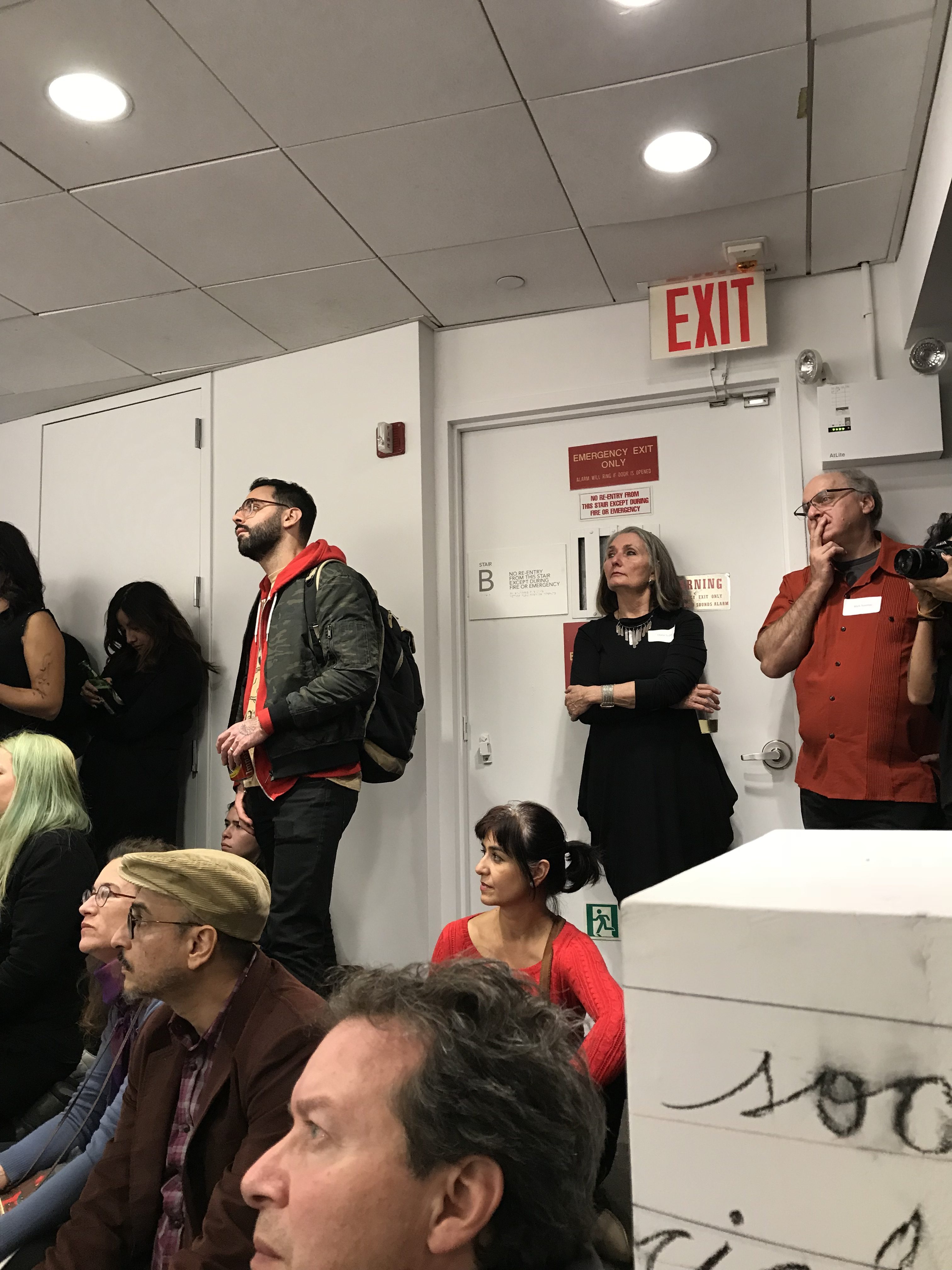

Photo Caption: I want to demonstrate an image from one of my personal artistic methodologies of “walking with others,” as a photographer. Although Diana Taylor did not authorize this photograph of her, as I finish reading the essay ¡Presente!, I now know what struck me to take this photo at the time. Diana Taylor’s pose watching Deborah Castillo, aka Profunda, perform the piece “Marx Palimpsest” in her own Institute: her lifelong’s work of “walking” in “performance” with those made marginalized, made fugitive, criminal, subordinate, and most importantly colonized. She is in loud silence, by the door’s exit. Arms crossed, but also joyfully holding her copa, eyes open to see, but focused, eyes on the performance but also a patient creator-spectator in her own party: she is present/e!. The amount of people in that space from different walks of life, is evident that, Taylor practices what she preaches, so to speak.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Boderlands: La Frontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Book Company, 1987. Print.Paz, Octavio. The Labyrinth of Solitude. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1985. Print.

Paz, Octavio. The Labyrinth of Solitude. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1985. Print.

Taylor, Diana. ¡Presente!