TABLE OF CONTENTS

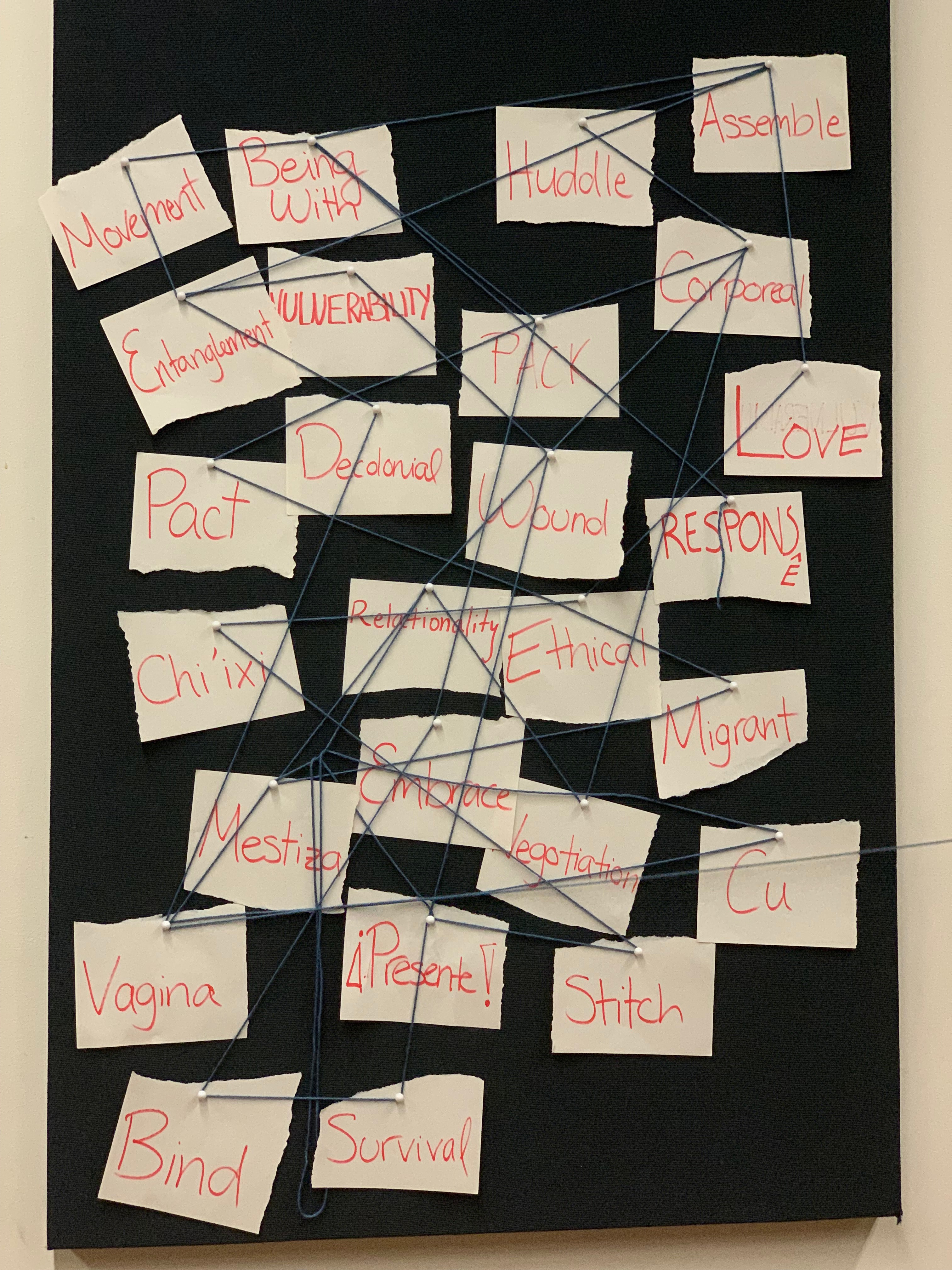

I. Vulnerability – II. Pact – III. Relationality – IV. Response – V. Pack

INTRODUCTION

A giant white sheet floats around the city. The fabric is punctuated by heads from the participants of this collective performance. Their bodies are hidden under the cloth. To accomplish movement, these strangers must try to synchronize their steps and, together, they must find a common direction. This image is from a performance of Lygia Pape’s Divisor. The Divisor creates a mutant collective being, but also maintains the individuality of its participants: one can decide to dance, to jump, or leave and be substituted by another. It is from this initial image that we head towards the goal of our collaborative project: to propose a few possibilities of “Being With,” how we can be together, knowing that there are many more and that the project in mind will always be a work-in-progress.

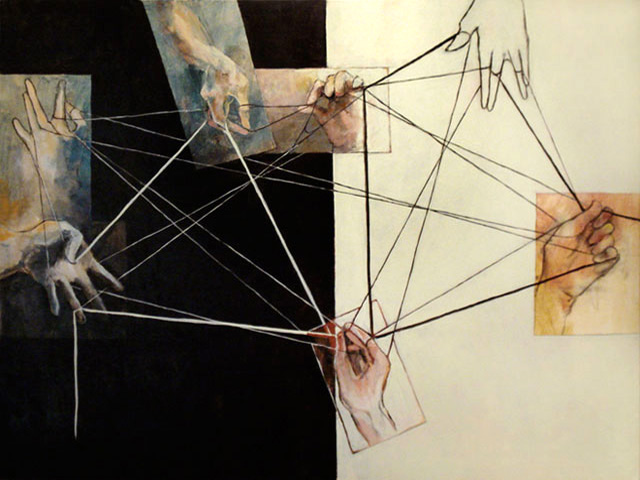

In this project we propose five intertwined decolonial practices stitched together by the politics of entanglement: vulnerability, pact, relationality, response, and pack. Like participants in Divisor, we move in a heterogeneous togetherness through an interdisciplinary methodology: we develop our core concepts and the web of interactions in ensemble yet, as each Divis-ee would traverse their own line of pavement, we move singularly over our chosen terrain (art, current events, dance, performance, theory), sometimes meeting each other in intersecting pathways. Divisor is not just a conceptual point of arrival; it requires of us an embodied togetherness borne from constant negotiation, so we also work together to develop physical explorations of our concepts: Cat’s Cradle, String Mapping, and the Dowel Exercise.

VULNERABILITY

In (re)thinking vulnerability and how it has been mobilized in the decolonial field, it is possible to notice the emergence/y of the corpo (cuerpo/body) as pivotal to the contemporary debates on neo(colonial)liberal dynamics, especially in regards to the affective dimension of our political lives in the Americas. From Gloria Anzaldua’s US-Mexico border as “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds”, to Eduardo Galeano’s “venas abiertas“ (veias abertas/open veins), Latin America counter-discourse on the “coloniality of power” often points out to the materiality of a ferida aberta (open wound) – a resilient sore that shapes the overlapping lines of continuity between colonialism and current structures of subordination.

If we borrow Achille Mbembe’s definition of postcolonialism as a demand for a “politics and ethics of mutuality”, a critique to Eurocentrism and a call for ethical intervention, we will stumble upon the complex inscriptions of the private body into the public sphere of former colonies. As a continuum bodily/bloody conflict that challenges the sociopolitical global order, on the gendered and racialized bodies of Brazil – a former Portuguese colony – especially, the colonial wound enacts the biopolitics of life, the violence that accompanied imperialist expansions and outlasted till the present, exposing the unsaturated fractures of the nation’s political body.

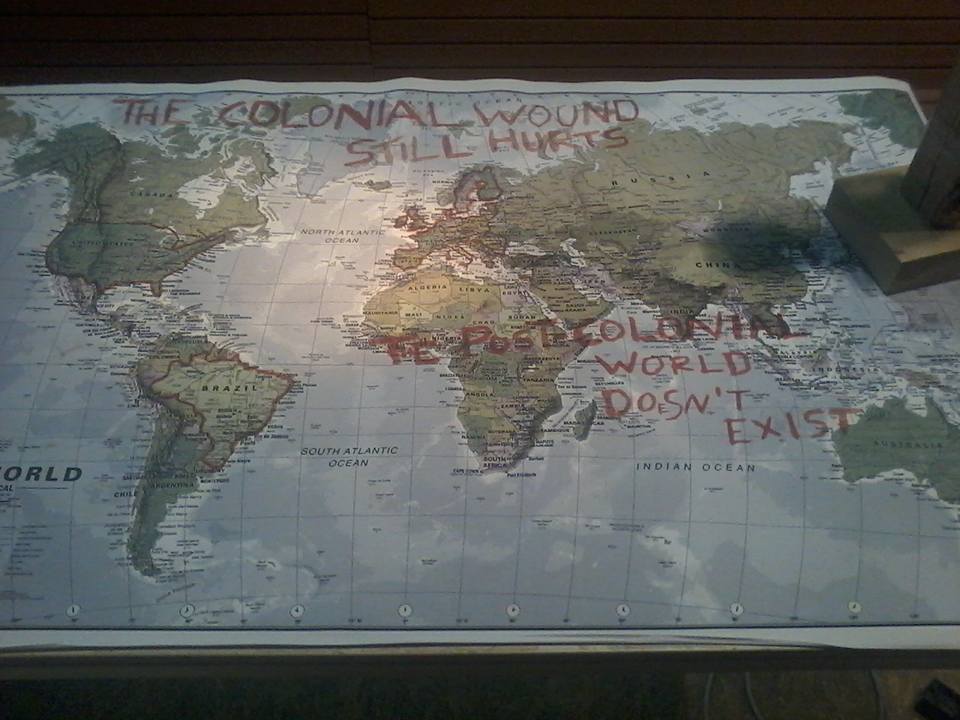

As Jota Mombaça writes with the artist own blood on top of a map: “The colonial wound still hurts. The post-colonial world doesn’t exist”.

As it asserts itself as a bodily fluid with the potentiality for tainting everything it touches as it spreads around the geographically constructed body of the world, blurring and redefining its borders; Mombaça’s bloody inscription emphasizes the correlation between territorial conquest and violation (both corporal and pictorial), challenging the euro-centered cartographic representation of the world through its modes of visibility. Mombaça’s intervention operates in order to redefine this visibility, for there can be no postcolonial world while the colonial wound still bleeds.

In all its political and affective intensities, the wound of colonialism implies imposed injuries, painful interpellations, modes of subjugation, conflict, and erasure, but it also indicates a way for thinking the materiality of embodied political resistance without disavowing vulnerability and the gendered, sexual, and racial implications of “one’s bodily exposure to one another”. For the idea of a fractured subject immediately collides with the sovereign account of agency by the unitary, self-determined, transparent “I”: the Post-Enlightenment subject that enacts the mastery over the domain of life by regulating the grammars of power that constitute the “Other”, rendering it as a product of universal reason.

When we look upon the Americas today, in light of heightened processes of precarization conducted in the name of neoliberal rationality and necropolitics, and we find ourselves in the need for new forms of alliances in order to resist “becoming precarious”, urgent questions arise: Can a sense of ethics emerge from vulnerability? Can vulnerability inform us towards the creation of ethical alliances?

As Judith Butler writes:

“I am wounded, and I find that the wound itself testifies to the fact that I am impressionable, given over to the Other in ways that I cannot fully predict or control. I cannot think the question of responsibility alone, in isolation from the Other (…) That we are impinged upon primarily and against our will is the sign of a vulnerability and a beholdenness that we cannot will away. We can defend against it only by prizing the asociality of the subject over and against its difficult and intractable, even sometimes unbearable, relationality. What might it mean to make an ethic from the region of the unwilled? It might mean that one does not foreclose upon that primary exposure to the Other, that one does not try to transform the unwilled into the willed, but to take the very unbearability of exposure as the sign, the reminder, of a common vulnerability, a common physicality, a common risk.”

Vulnerability, when thought as an ontological concept that points to the emergence of ethical responsiveness “in-between” bodies, signals a new terrain of relations between the aesthetic and the political, from which new images of the common are possible and displaced towards new organizations of the sensible.

In this section, as we approach the challenge of “being with” in the quest for what could be considered an ethical alliance in our historical present, I would like to invite the reader to enter this colonial wound with me in order to explore its openness; And to see where it may lead us in the search for new gazes towards the present. I must warn you, though; (For certainly) the path will be sticky and you will probably get blood on your shoes.

In Adriana Varejão’s two versions of Filho Bastardo (Bastard Son), on the left side of the oval canvas, we see a priest copulate with a half-dressed slave, pressed against the trunk of a tree. On the right side, two military figures attack a naked indigenous woman whose hands are tied on a branch above her head. The pictorial composition – a kind of mimicry of the colonial representation made by the French artist Jean Baptiste Debret in his series “Picturesque and Historical Journey to Brazil” (1834-1939) – is desecrated by a central cut, irrevocably evoking the form of a vagina. The violated canvas performs the violence it portrays and, in its opening, in the particularity of the form it evokes, the layered cut positions the vagina as a place of enunciation: the birthplace of the racial ideology of the mestiço (mestizo), the nation’s bastard son depicted in the title of the painting, born from an indigenous and African womb and destined to serve in the purpose of “whitening” the nation.

Varejão is a white descendant from a Portuguese family and one of Brazil’s leading contemporary artists – one of the most expensive too. You should have this in mind as we go on, for the complex figure of the mestiço is a central character for understanding Latin America’s specific mode of colonialism.

Different from Gayatri Spivak and Homi Bhabha’s canonical critique on Great-Britain-India coloniality, in order to properly understand Latin America’s mode of subaltern production one must acknowledge the intricate lineage system – bodily fluid rather than culture alone – that rendered the mestiço not only as an inscription of race in the so-called Novo Mundo (New World) but also as a social parameter for the distribution of vulnerability.

Like the map profaned by Mombaça’s blood, which blurs the geographical borders as it disavows its social order construction, Varejão defies the historical discourse of the Brazilian miscigenação (miscegenation) commonly portrayed as a social democracy, evidencing it as a discursive construction built upon violence and violation – And precisely through violence and violation, as the artist shows, it can also be exposed, dismantled. For in Bastard Son, Varejão opens before us the womb of the Brazilian colonial history: the genealogy of the mestiço subject, tropical and precarious, bond in a twice-vulnerable vulnerability, for it inherits the subject position of the African and indigenous’ womb in the racialized social order, while at the same time gives body to the subaltern’s subjugation. The torn vagina thus presents itself as the birthplace of the nation, an entry gateway, but also an exit site, a primary locus of enunciation for the subaltern.

That is to say that from the wounded womb that generates the nation’s bastard son, the tropical-precarious mestiço, Varejão renders the open vagina as a site equally or more destabilizing than the mouth itself, on which Jacques Rancière wrote as the place from which “politics comes when … the mouth emits a word that enunciates something of the common and not only a voice that signals pain”. According to Rancière, the refusal to consider some categories of people as political beings – namely, women, slaves, animals, and children – always went through the refusal to “hear the sounds that came out of their mouths as a discourse”. Viewed in this way, the torn vagina in the painting becomes an essentially political place, because it threatens to redistribute the visible and audible as it materializes the opening through which the subaltern colonial subject’s speech can be heard. The mestiço’s body manifests not only the product of a violation but also the materiality of the subaltern’s speech, the living-breathing-bleeding form of life it creates.

So as our journey leads us through the abyss of the openings of the body, through the body as something that opens itself up; we must then ask: what can an open body do?

Marielle Franco was a black lesbian woman born in favela da Maré, a place considered one of the most dangerous favelas in Rio de Janeiro, inhabited mainly by the so-called Brazilian mestizos. In 2016, she was elected City Councilor with 46,502 votes – the fifth highest vote that year. Marielle believed that occupying politics was fundamental in order to reduce inequalities, the very ones she had experience throughout her entire life. She was a human rights activist, who constantly criticized and denounced police abuses and civil rights violations, particularly when it occurred in the most vulnerable areas of the city. Her political platform was based on the promise to give voice to the black and peripheral minorities of Rio de Janeiro, especially women, especially queer.

On March 14th 2018, Marielle was executed with 13 shots: 3 in the head, 1 in neck, while the others pierced her car, also assassinating Anderson Pedro Mathias Gomes, the driver of the vehicle. At the time of her death, Marielle had just recently been nominee chair of the Women’s Defense Commission, whose objective was to monitor the federal military intervention that was currently taking place around the State of Rio, but more actively inside Rio’s favelas. According to investigations, the precision of the shots that fractured Marielle’s body, the technological failure of the security cameras on the street she was killed, the sophisticated kind of weapon that was used in the shooting and the fact that there was another car giving possible coverage to the shooters, strengthened the hypothesis of a premeditated crime.

On the day following the announcement of her death, more than 20.000 people gathered around the streets of Rio de Janeiro to protest and to grieve together, exhaustingly screaming the words “Marielle Presente!” (Marielle Present!) and asking the question: “Quem matou Marielle?” (Who killed Marielle?) over and over again during the entire night.

Almost eight months afterward, the police and the ongoing federal investigation are still not able to respond to the question that haunts the streets of Rio de Janeiro: Who killed Marielle Franco?

As we begin to reach the end of our journey (and the final of this section), the carioca artist Flávia Naves is starting the 200th day of her performative ethical intervention, a single action that takes place throughout the public spaces of the city, where Naves relentless asks the unsolved question – a phrase painted over on top of her clothes.

In one way, Naves’ ethical intervention is questioning the duration of the public protest, its modes of gathering people around and the effectiveness of its performance in regards of generating consciousness in a more everyday environment; On another, she is turning the public protest into an unmanageable source for the repressive forces of the State that so often violently contain political antagonisms; even though Nave’s pursuit for justice is not a claim made towards the State itself. Rather, the question of Marielle’s death is being addressed directly to the people of Rio de Janeiro, holding them accountable while at the same time reminding them that Marielle’s execution is a common problem of the city’s necropolitics, a common risk by which all common citizens are subjected to and rendered vulnerable towards. Naves’ action is an ethical claim because it understands that if the political sphere can no longer account for people’s life, if it is corrupt and untrustworthy, then is the people that you should be talking to. They are the ones that you should get involved.

Naves is committed to an alliance with Marielle’s dead body, but most importantly, she is committed to an alliance with the people of Rio de Janeiro. A commitment that she has to reaffirm every morning when she chooses to lend her body as an enunciation site, defying the State’s necropolitics by transforming herself into a channel and an antenna that amplifies the sound of Marielle’s death and its implications to the citizen’s common life. That is what makes an ethical alliance possible.

For an ethical alliance is never a fixed or stable state, it demands constant participation in the form of a commitment. You have to be committed in order to act, as an ethical alliance is always about acting. So you have to commit yourself once and over again for it will only cease once you stop committing.

An ethical alliance does not seek the State or any sort of political institution as its interlocutor; it is a bond between two (or several) beings capable of action, living or dead, humans or non-humans. An ethical alliance is a coalition based on the realization of life’s interconnectivity and interdependence (the holistic truth neoliberal capitalism so desperately wants us to forget); And it operates through an equal, common goal: to enhance one another’s potentiality to act.

An ethical alliance does not imply similar responses for every being involved, nor similar kinds of actions from each part. A being never loses its own singularity in an ethical alliance, for an ethical alliance can never become homogeneous. If it becomes homogeneous, then it is not an ethical alliance (those are the kinds we should be attentive and vigilant about!).

Naves’s performative action – this personal and, at a first look, completely banal political form of protest – of simply walking around the city with a phrase inscribed in her shirt, allows for the opening of different paths and possibilities for a collective map of resistance made of action-thinking – (that is, to think dangerously, as Aimé Cesaire puts it), – for Naves affects everywhere and everyone that she encounters simply by posing one question. After all, as Diana Taylor once asked, “What to do when there [is] nothing to be done, and doing nothing [is] not an option?”. In moments like this, sometimes the best we can do, or the only thing we can actually do is to make ourselves present and to be sure that we understand the ethics that the present is demanding of us.

Thank you for entering this wound with me. You may leave for the next section now.

PACT

A pact has to be entered into and inhabited. Although entering into a pact often involves a mutual crossing of the threshold between informal and formal alliance, this process is never complete since formality requires the kind of shape and definition that essentializes and reduces. A pact is performative in the Austinian sense. It is beyond the noun, a formal document of the archive – it is an ongoing series of actions, the continual embodiment of an alliance. We could say that it is one movement in the repertoire of decolonial practices. A pact is a decision, but one that must be renewed over and over (and over) again at every juncture and crossroads or else it becomes a doing to rather than a doing with. A doing to is not a pact. Because a pact never stops being reborn in this way, a pact is not a static entity but rather performs the precarious space between humans and their needs and desires. In our exploration of “being with” and what it means to form alliances, the concept of the pact considers the structures that bind people under a common need and/or desire.

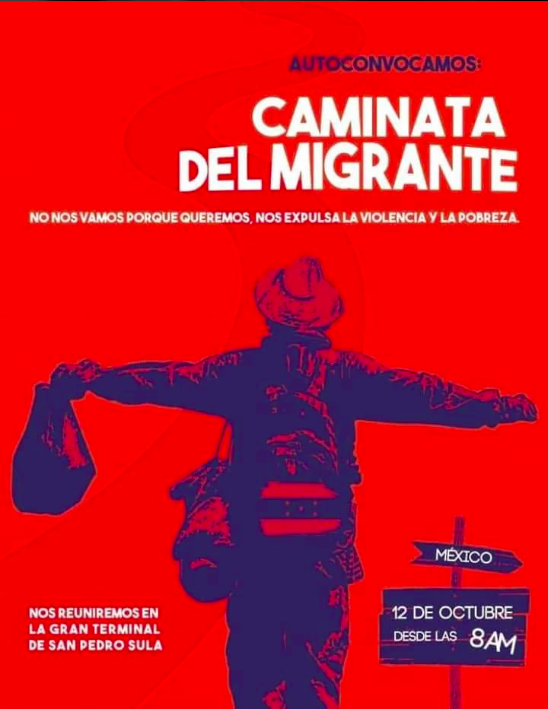

“Autoconvocamos: caminata del Migrante”

“We assemble ourselves: migrant walk” announces a bright red flier in large block letters. Beneath this summons, “No nos vamos porque queremos, nos expulsa la violencia y la pobreza” (we do not leave because we want to, the violence and poverty expels us). The image on the flier is of a single migrant carrying three bags. Arms fully extended out to the side as if to embrace or to fly, the migrant walks along a winding path past a signpost with two signs, one in the shape of an arrow that reads México, the other bearing a date: 12 de Octubre desde las 8am. The bottom left corner of the poster reads Nos reuniremos en la Gran Terminal de San Pedro Sula (we will meet at la Gran Terminal of San Pedro Sula). This call to action was circulated on social media platforms as part of a wider, open invitation to convene a migrant caravan in Honduras which would travel as a pack through Guatemala and Mexico in the hopes of reaching the United States. An unprecedented number of people have since joined this caravan – which is not the first of its kind – as those who had long considered making the arduous, expensive, and dangerous journey jumped at the opportunity to pursue safety in numbers.

In formulating what she calls a mestiza consciousness, a “consciousness of the Borderlands,” Gloria Anzaldúa imagines a gathering at a crossroads,

“that juncture where the mestiza stands, is where phenomena tend to collide. It is where the possibility of uniting all that is separate occurs. This assembly is not one where severed or separated pieces merely come together… In attempting to work out a synthesis, the self has added a third element which is greater than the sum of its severed parts… a new consciousness…”

The juncture that Anzaldúa describes works at the level of the individual, but it is also depicted visually in the flier mentioned above. A lone migrant stands poised to enact a life-altering decision to walk and to keep walking. The digital migrant’s body, opened up at the heart, solicits a coming together of previously severed elements and in doing so provokes a collision of real, living bodies. The migrants of the caravan comprised of these living bodies do not simply gather together, but continually attempt to work out a synthesis so as to mutually achieve their shared goal by moving together more or less as one entity. The work of achieving a synthesis may never be complete (not everyone can move in the same way or at the same pace), but it is in the habitually and collectively renewed decision to keep going – to become “greater than the sum of its severed parts” – together that the migrant caravan that left San Pedro Sula on October 12, 2018 enacts a pact.

If a pact is the continual embodiment of an alliance, not just a “being with” but a “doing with,” what does this doing with look like? For the migrant caravan, it looks like walking. Thinking also of migrants south of the U.S. border, Diana Taylor theorizes around walking in ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence,

“the walkers do not see the goal clearly ahead of them. They follow the promise that they will recognize the place when they come to it. And, the walkers’ bundles make clear, we never walk alone, even when solitary… their bodies, like ours, transmit traces of familial, group, and territorial belongings… They, like us, carry their worlds with them even as they venture into the unknown.”

For the thousands of Central American migrants who joined the call to convene as a caravan this Fall, their goal will always be “clearly ahead of them,” located on the horizon even when and if they reach the U.S. border, even when and if they cross that border. As migrants (as walkers) they will always be at risk of further expulsion, further violence, and further poverty. Yet, the flier declares “we assemble ourselves.” This is an ongoing experimentation in decolonization. It is a collective embodiment of the decolonial tactic of the pact. To assemble is to join separate parts together into a composite machine. In the case of the migrant caravan, spurred to join an anonymous comrade already in motion with open arms, three bags, and a strenuous road ahead, the composite machine attempts to forge and reforge new territorial belongings from previously singular pasts.

RELATIONALITY, OR MOVING TOGETHER

How can we move from the individual “I” that capitalism privileges in the spirit of competition and profit to a collective “we” bound by mutual respect and based on our inherent relationality? Central to this action is the realization of the distances that exist between us in the current neoliberal order and the importance of closing these distances before we can truly “be with.” This section analyzes relationality through movement, specifically the movement inherent in closing the distance and how we can learn to move with others. In everyday life, we are always –even if inadvertently so– involved in pacts of movement; we are vulnerable to each other’s gestures and respond to them, we move as assemblage, bricolage, a pack…What we keep returning to here is a new relationality –or awareness of the inherent ways we are all connected to each other– in the face of ongoing colonialities of power (Quijano) tied to the violence of erasure on the basis of difference. Therefore, being together, closing distances, becomes an intimate form of radical resistance against the state of division that characterizes our current world.

How can we approach what Boaventura de Sousa Santos names a radical copresence (191) through the lens of movement as moving WITH OTHERS? In order to reach a true state of solidarity, de Sousa Santos emphasizes how we will need to “be with”, “knowing with, understanding, facilitating, sharing, and walking alongside” (ix). Diana Taylor, in ¡Presente!, presents a methodology of walking in order to fully “be with” one another. All of the actions outlined emphasize a collective we and relationships of responsibility; here, the I only emerges to be with another.

Susan Leigh Foster examines this paradox, asserting that deeper awareness of one’s own movements––logically, an intensely introspective and therefore private ‘lived experience’ of one’s own body––actually allows access to understanding how another moving body might feel, a body that is external yet at the same time continuous with the subject…Kinesthesia, in short, implies an intimacy with the other that is sustained by an intimacy with the self.

-Carrie Noland, Agency and Embodiment

In thinking about the act of coming into presence, it is impossible not to address the body, both one’s own body and the bodies of others. Thinking around Boal’s exercises, what is powerful about corporeal communication is that it involves a heightened sense of attention to one another, a deeper layer of coming into presence, hacer presencia. I can talk to you with my back turned, but if we are communicating through our bodies, if you are following my hand with your face, there is no chance that we can establish a dialogue without facing each other, without following each other’s movements and developing a shared rhythm-dialogue. Carrie Noland’s conceptualizations of the gestural self and embodied agency further remind us of the importance to physically be with each other in everything we do– and to be in touch with an intimacy with the self– we may read this intimacy as an exercise in vulnerability, an unmasking in a way. In attempting to answer –at least partially– the question of how we can “be with”, this section finds dance to be especially pertinent to understanding both our own body and how our bodies share space.

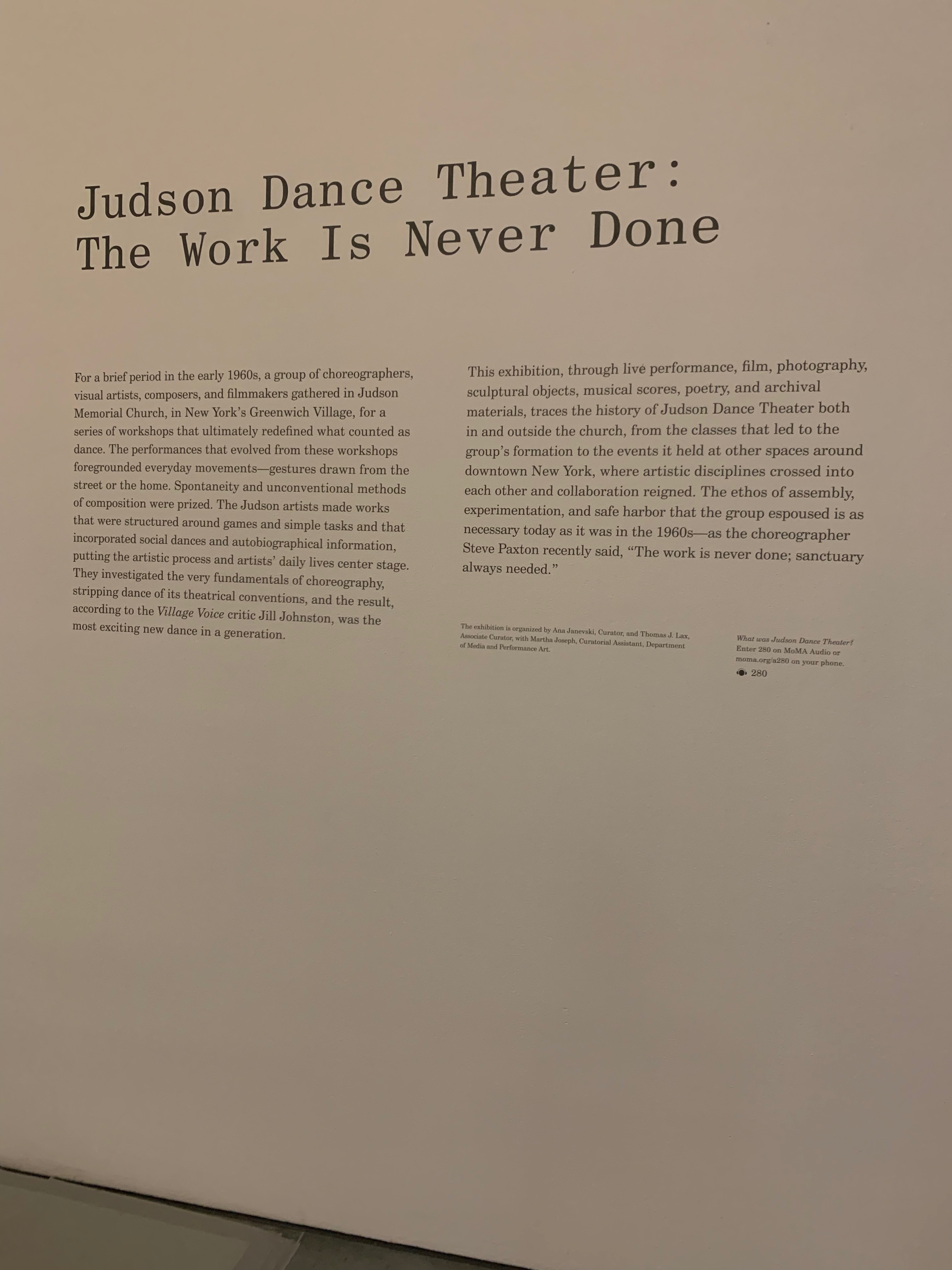

“The work is never done; sanctuary always needed.”

-Steve Paxton

Simone Forti, the American Italian Postmodern artist, dancer, choreographer, and writer, began her dancing career in the mid-1950s. She is known for her 1961 body of work, Dance Constructions –currently on view at MoMA–, highly participatory and pedestrian-accessible dance interventions that destabilized the concept of traditional dance forms.

In one of her most well-known constructions, entitled Huddle, a group of five to nine performers form a mountain through the act of the huddle, and take turns climbing over the top and coming down the other side. As curator Stuart Comer suggests, Huddle is “highly participatory and suggests the way that notions of community were being rethought during the 1960s…at a moment where collective action had become central to political life of the United States. Huddle was a way of encouraging reflection on what happens when a group of people come together and how they negotiate each other.”

Being With is a movement that requires continuous negotiation; moving together in Huddle is not a fully harmonious process; rather it means a constant straining and strategizing on the part of the foundation of many bodies –a foundation never in stasis– and the arduous movement of climbing over and coming down the other side; an individual movement, yes, but one that is achieved through the support of the other performers and one that each participant, in turn, will be able to experience in their own way. Being With is a slowly negotiated process; the performers in Huddle hold each other tightly, getting accustomed to breathing together, being with one another, before the first performers ready their ascent. The process of climbing involves a calculated series of movements; the climbers will slowly separate themselves from the foundation –and the performers in the base will immediately come together to close the gap–, then, the climbers will ascend with caution, taking their time to feel-move to the other side, always staying close to the base, sometimes moving only on their stomachs, before landing on the ground and being held back into the foundation with care, through a gentle yet protective gesture of the arm. Here, then, slow movement works in a similar way to what André Lepecki has argued as a destabilization in certain dance forms of “the kinetic project of modernity…aligned with the production and display of a body and a subjectivity fit to perform this unstoppable motility” (3). Being with through slow movement allows for a variety of becomings: the climber stops for a moment to readjust the hair of one of the members of the foundation, for example. Gestures, as Noland suggests, can be “intentional or involuntary, crafted or spontaneous” (6). Here, the process of becoming also includes a sensuousness that develops both within one’s own body, and with the bodies of others. As the climbers each find their own path, it is a process that is only possible through the acknowledgment of all the bodies involved: the realization that we are all connected.

Huddle requires being intimately presente: to your own place in the living structure, to how you are interlaced with the bodies next to you, to how you are supporting the body moving on top of you, all a negotiation between bodies, movement, and their responses, a negotiation nonetheless that comes from the gesture of a tight embrace, a gesture of love. If, as Lepecki argues, dance studies allows us to “consider in which ways choreography and philosophy share that same fundamental political, ontological, physiological, and ethical question that Deleuze recuperates from Spinoza and from Nietzsche: what can a body do?” (6), I follow that dance also works to answer the question:

What can bodies achieve together?

In Huddle, the mass of bodies that come together transcend a mere moving sculpture; rather, they create a living shelter –especially when the construction is performed outside in the cold, Forti explains– through negotiation where every participant, and every gesture that they make, in turn creates the ability and success of moving together.

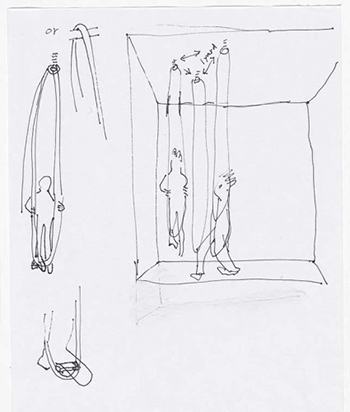

The other dance construction I would like to examine is Hangers. Forti describes this intervention as “a meditative piece. There are three ropes attached to the ceiling in a triangle—they hang down and loop. And there are seven performers: three stand in that loop of rope and four people walk between the hangers. I sometimes almost think of it as a wind chime in terms of the kind of walking through…The whole thing is moving. It’s breathing.”

Hangers serves as an interesting contraposition to Huddle because although it seems like a more passive piece, it too involves active negotiation and demands a being presente to the nuances of movement and gesture. Those hanging on the ropes must balance their bodies and learn how to move through rocking; a movement that sometimes can be turbulent as the walkers pass and bump or brush against the hangers. The walkers must constantly find new and improvised paths in a confined space, negotiating these pathways with their fellow walkers and hangers. The whole construction moves together, and demands a being presente both through moving and seeing. The participants watch each other’s movements, bodies, footsteps, sometimes anticipating them as they position their own bodies and respond to each other; negotiations happen as bodies make contact with and walk past each other. The movements seem pedestrian because they are: we repeat them everyday, walking down the street, participating in the sidewalk ballet, as Jane Jacobs would call it, improvising paths, walking the city, following De Certeau, but not always presente when we are separated through a screen, for example. When we are presente, our bodies seem to recognize its coexistence with others even when we are rushing to our next stop; the way it swerves, brushes, and sometimes bumps against other bodies speaks to a constant negotiation of space and place as we respond to the material reality of being with.

De Sousa Santos suggests that “our knowledge flies at low altitude because it is stuck to the body. We feel-think and feelact” (12). Here, he brings the body, “feeling,” both into thinking –epistemology– and acting –action–. In using an epistemological framework that centers the body, and here, many bodies, and thinking around Forti’s Constructions while keeping the image of the Divisor in mind, I would like to emphasize the constant movement and negotiation, with others, at stake in everyday life, and how “being with” involves, as Taylor conceptualizes, “betweenness and negotiation as integral components of thought and presence” (5).

In considering how we can truly “be with”, it seems like a good start to return to the body, and think about how it speaks to, and moves, with others.

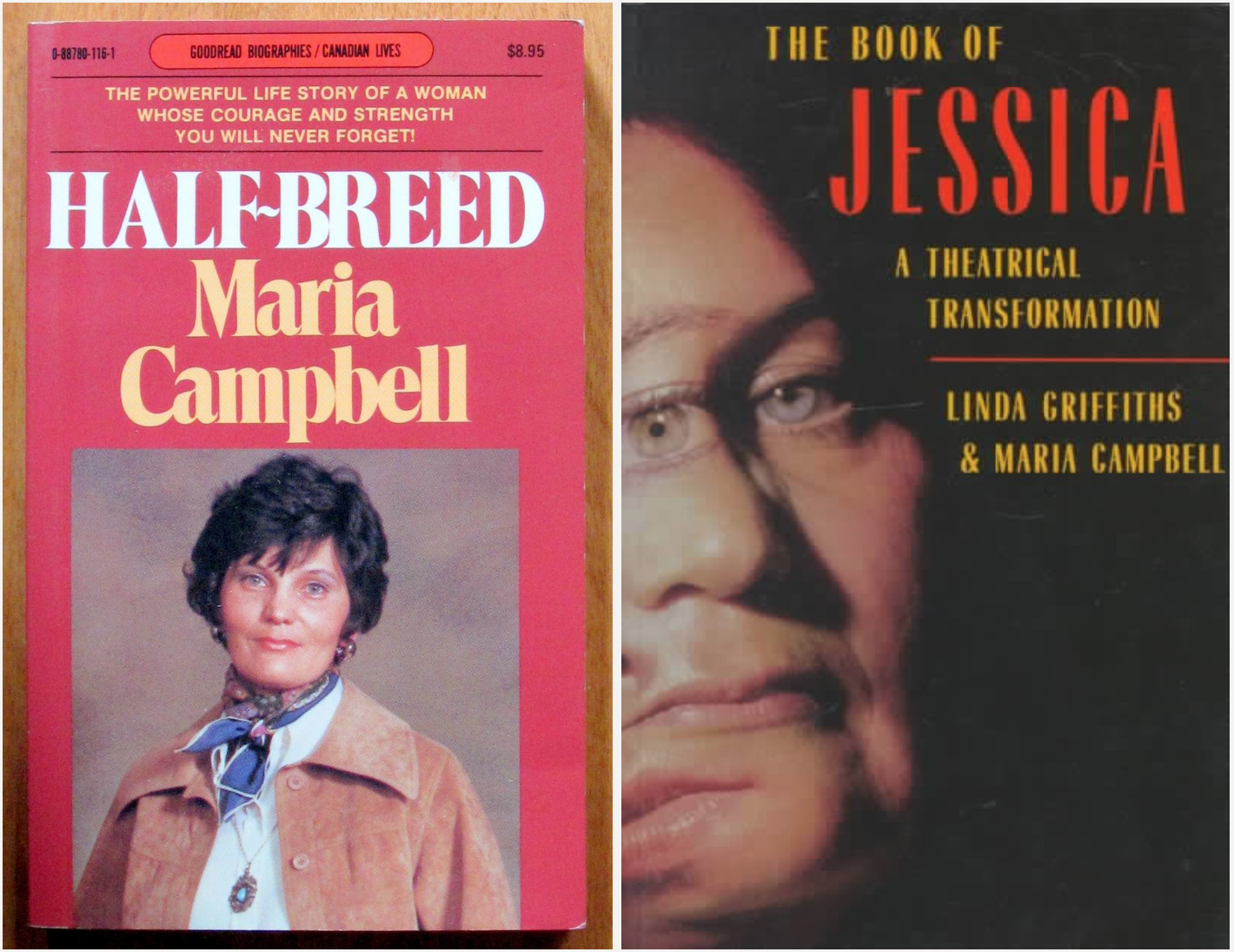

RESPONSE, OR SURVIVING THE WOUND

Central to performance studies is Richard Schechner’s theory of performance as twice-behaved behavior (1). Fred Moten expands that idea proposing that perhaps it is in the space between those moments of behavior that performance occurs, that the space shares a kinship with Kaprow’s art-life blur (2), and asks how do we respond to one another ethically in the midst of the art-life blur (3)? Written by Linda Griffiths and Maria Campbell, The Book of Jessica is an unflinching record of the 15-year creation process of one of the most significant pieces of Indigenous theatre created in Canada. In various written forms, the book details the rehearsal process of the play Jessica, wherein white actress, Linda Griffiths, improvises scenes from Metis activist Maria Campbell’s life before Maria’s very eyes. The book highlights the necessity and difficulty of vulnerability, alliances (pack & pact), negotiation, and relationality as necessary elements of “response.” In the art-life blur of The Book of Jessica, responding with precision is an ethical imperative.

In an extraordinary example of twice-behaved behavior, Maria Campbell lives her life multiple times: in the originary, running with the mark of “half-breed” from a one room cabin in Northern Saskatchewan to Vancouver’s red light district to the life of indigenous activist; in memory, writing the autobiographical account of her life in “Half-breed” (4); in subjective transfer, training actress Linda Griffiths to portray “Maria” onstage; and in collaboration, writing the performative history of that production in The Book of Jessica. Constant re-livings of Maria’s life enact a series of punctures, moments that exemplify “twice-behaved behavior.” But between each glistening point of “behavior” is a warm blur, the blood beneath the needle’s prick, an intermingling in the disrupted boundary of art and life. Each life, each behavior, is a wound that opens up space for encounter.

MARIA: I remember when I was a little girl, and we were going to a Sun Dance, and there was a ‘give-away’ after…. The day before [my grandmother] had given me some cloth for a dress. It was very special, it was a print, but it was the colour I wanted, red. I knew my grandmother knew how much that cloth meant to me… You see, your most prized possession should be what goes to the give-away. So I made a big deal about looking through my stuff… trying to fool her into believing that something else was more important than the cloth…. My grandmother never said anything, she was just sitting there looking at me while she smoked. She knew what I was doing and I was ashamed. I put the cloth on the blanket and I started to cry. I knew I wouldn’t have a new dress. My grandmother waited until I finished crying and said, ‘The give-away should hurt, that’s your sacrifice.’ (Campbell and Griffiths, 110)

Maria sacrifices in re-woundings, the wound serves a greater purpose: that others may learn from her experiences of living with mixed blood, living in and between cultures. In a quilting circle, the needle pricks away with precision, wounding the fabric in order to cinch it together. Women could taste the phantom blood on the quilting needle between their lips and offered support. Maria does not wound alone, her pack of hummingbird women help to wound and bind (5). The quilting circle itself is a bind, the work of women, their shared agreement to complete this gift-sacrifice, is a binding pact. The primary bind is between Maria and Linda, who labor to create a gift for the community.

Wound. Use. Bind. Sacrifice. Rehearsal is a bind. To rehearse is to be perpetually in a bind, to live in a problem. To bind or entangle the filaments of a production (of a body, of the productions of a body) into a performance. To be in a bind, wrestling with a problem: how can I be you? How can white be red? How can this be that (6)? How can that survive this?

LINDA: Maria was experimenting with the makeup I would wear in the show. It was advisable to, as Paul put it, ‘brown up’. Maria decided we should put me to the test. There was a graduation of high school students at Native Friendship Centre and she took me there as her guest. Before we left, we worked on my makeup. It was strange, but when I looked at my face, there did seem to be a change. Was this ‘Brown like Me’? But I felt relaxed around Native people in a way I’d never felt before. It was like wearing an invisible cloak. I walked down the halls of the center feeling like a Native woman, treated as a Native woman. Maria whispered instructions to me but, as she said later, I could easily have been a Halfbreed who had been brought up white. At one point a white man came into the room. I couldn’t believe what I felt. Everyone pulled in, as if to protect themselves. I pulled in too, in a moment of complete identification. Maria leaned over and said. ‘Now you know what it’s like. If you’d come into the room as a white person, that’s what would have happened.’ We went to the washroom at some point, and she got out her makeup and did a touch-up quite openly, without the least sense of embarrassment. We were laughing like schoolgirls, as she blended in the streaks on my face. (Campbell and Griffiths, 45-46)

The above paragraph contains content that is problematic to say the least. The reader will likely sit up straight at this blatant mention (and use) of brown face. A white woman literally paints her face darker to gain entry to an indigenous event. Even though this is suggested and facilitated by a Metis woman, a leader in her community, it is not easy to reconcile this situation. And I don’t mean to reconcile it, the events in the account of rehearsing Jessica are incredibly complex, constantly testing the boundary between ethical and unethical creative processes.

Brown face, or red face, is a violent act of cultural appropriation. Italian actors playing indian warriors in classic hollywood films (hence the term “Spaghetti Western”) and sports team mascots like the Washington Redskins, cast the “indian” identity as an object to be bought and sold. In fact, it was a red face performance of another Canadian Indigenous play that inspired Maria to respond and, as Peggy Shaw would say, “make [her] own fucking play” (7).

So where is the ethical position in this questionable rehearsal practice? In rehearsal, Maria uses brown face as a mask, allowing herself, her brown skin, to be used as an object. In ceremonies, masks are often used as transitional objects. Yet, is it the make-up or Maria that is the transitional object? Employed by and between Linda and Maria, the boundaries between skin, make-up, and mask blur together as these elements, liminal by nature, enter the bind of rehearsal (8). Time and time again, Maria rejects a respectful distance in rehearsal, showing that restraint is not the only form of ethics (9). Barbara Johnson suggests that, perhaps, Winnicott’s transitional object is not just a thing to be used (a means to an end) but that “the capacity to become a subject [is] something that could best be learned from an object” (10). Johnson then highlights the necessary distinction between object relating and object use by approaching Winnicott’s metaphor of subject as patient and object as analyst: “some patients, it seems are unable to “use” the analyst. Instead, they “relate to” the analyst by constructing a false self capable of finishing the analysis and expressing gratitude. But the real work has not been done” (11).

Avoiding the “real work” of using the analyst in order to develop as a subject belies a lack of respect–an assumption that the analyst is too fragile to survive its own use. In performance, this translates to tokenism, cultural tourism, or performances that could be said to suffer under the death grip of reverence. Maria is working to avoid her own museumification. Through the use of mask as a transitional object, Maria creates an intermediate position between the subject and the object yet “the intermediate position is not in space but in what it is possible to say” (12). Linda notices that with the mask she is able to act with “complete identification.” In fact, as Linda is able to “say” more, the mask, bit by bit is destroyed yet “the properly used object is one that survives destruction” (13). This is because the object is not destroyed so much as the subject’s perception, or fantasy, of the object (14). The ethical imperative of using people relies on this destruction of the fantasy of the other:

Perhaps a synonym for “using people” would be, paradoxically, “trusting people,” creating a space of play and risk that does not depend on maintaining intactness and separation. It is not that destructiveness is alway of and in itself good–far from it. The unleashed destructiveness of exaggerated vulnerability or of grandiosity without empathy is amply documented. But excessive empathy is simply counterphobic. What goes unrecognized is a danger arising not just from infantile destructiveness but from the infantile terror of destructiveness–its exaggerated and paralyzing repression. Winnicott describes the process of learning to overcome that terror, which allows one to trust, to play, and to experience the reality of both the other and the self. And this, it seems to me, suggests the ethical importance of “using people.” (Johnson, 273)

Out of blurry streaks of make-up comes the precision of a perceived difference, yet this difference is not contingent upon distance. From this point on, the respectful distance that might relegate Maria to the role of “fantasy” transforms into a proximal distance that allows Linda to more clearly perceive herself, Maria, and the space they inhabit. This proximal distance is the space for response, the space for rehearsal.

Ethical performance wounds for a purpose, uses necessarily, makes ties that bind, and sacrifices to give. Performers survive ethical use and are destroyed by anything other: like a square of fabric accidentally mangled during quilting, so too can a person be destroyed by their wounds. This is the bravery of Maria’s decision to wound, the wound for a tie, the tie that binds, the bind that holds, the hold that holds together, the together that transforms. Maria and Linda negotiate their wounds and bindings, they negotiate blending the streaks on their faces. The stitch of their stories binds as it separates: the squares of a quilt distinguish even as they blend into a new composition.

Notes

- Richard Schechner, Between Theatre and Anthropology (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1985), 36.

- Allan Kaprow, Essays On The Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (University of California Press: London, 2003), 201-218.

- Professor Fred Moten (class lecture, Critique of Opera, New York University, New York, New York, October 2, 2018).

- Maria Campbell, Half-Breed (Formac Publishing Company Limited: Halifax, 1983).

- Alexandra T. Vazquez, “You Can Bring All Your Friends,” Small Axe 20, no. 1 (March 2016): 185–193, https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-3481474.

- Shane Vogel in Stolen Time breaks down the term “this is not that” as a means of distinguishing authenticity and inauthenticity in black fad performance.

- Diana Taylor, ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming), 17.

- Victor Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure (Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, 1969), 69.

- Barbara Johnson, “Using People: Kant With Winnicott” in The Barbara Johnson Reader: The Surprise of Otherness, ed. Melissa Feuerstein, Bill Johnson Gonzales, Lili Porten, & Keja Valens (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014), 262.

- Johnson, 263.

- Johnson, 268.

- Johnson, 270.

- Johnson, 269.

- Johnson, 271

PROPOSAL FOR THE FORMATION OF A PACK

I want to compel all dogs thus to assemble together, I want the bones to crack open under the pressure of their collective preparedness.

Franz Kafka – Investigations of a dog

As already discussed, Lygia Pape’s Divisor seemed an important point of departure because it represented in a concrete and artistic way many of our theories and conceptualizations around the idea of being with. The writing of this spiderweb-like text was also, in itself, a gesture towards trying to promote the fugacity and movement that was such an important image for us all. It was as if we were performing a textual Divisor or performing an intricate cat’s cradle. It was a quilting of diverse point of views and ideas that also positioned us in the place that we were theoretically discussing: the place of being with, of being together for a period of time in which we would orbit around some similar key ideas, while also bringing other visions. This particular position reminded us of the discussion of the pack, as proposed by Deleuze and Guattari in their A Thousand Plateaus. In a pack there is also no homogeneity: the pack is nomadic, it is always moving both in a geographical sense and in its own structure. Its hierarchies can always be changed: the leader is not in a definitive position, but is always gambling this leadership, which is open for others to take. It is not necessarily always peaceful among its members, since they can fight among themselves, or even create other packs. There is always movement, always the risk of failure. The schizo dream told to us by Deleuze and Guattari and the evoked sensation of perpetual movement seems closely related to Pape’s Divisor:

I am on the edge of the crowd, at the periphery; but I belong to it, I am attached to it by one of my extremities, a hand or foot. I know that the periphery is the only place I can be, that I would die if I let myself be drawn into the center of the fray, but just as certainly if I let go of the crowd. This is not an easy position to stay in, it is even very difficult to hold, for these beings are in constant motion and their movements are unpredictable and follow no rhythm. They swirl, go north, then suddenly east; none of the individuals in the crowd remains in the same place in relation to the others. So I too am in perpetual motion; all this demands a high level of tension, but it gives me a feeling of violent, almost vertiginous, happiness.” (Deleuze; Guattari, 1987, p.29).

Can we learn something about this embrace of uncertainty and tension? Can this perpetual and nomadic movement, these frail alliances, allow us to think of new ways of being together with the other, while also trying to leave the constraints of thinking of this “being with” as only related with other human beings? How can we be open to this “violent, almost vertiginous, happiness” and to try to build alliances based on it?

The idea of the pack is precious for us because it dislocates the presumption that “being with” is only possible with human beings. As one can see in Adriana Varejão’s Filho Bastardo, previously discussed, nature itself was also affected by the colonial wound. From Amerindian Perspectivism (Viveiros de Castro, 2009) to the creation and promulgation of a binarist Human/Nature setting, which only propagated segregation, enabling the contemporary idea of the self-made man, the myth that Man is closed within himself, kept apart from the rest of the universe. One could actually see the conceptualization of Nature as a result of this wound, an infection that keeps spreading. But in here we trying to reflect on relations that would deviate us from the ones perpetuated by this Western epistemology. Relations that are based on this wound itself, in which rational men should unite with other rational men to achieve progress and/or revolution. We need to stop thinking of relations as only possible between equals, and in here we are not only speaking of equals in political views or identities, but also based on species: thinking politics as only suitable for Humans. We want to create a pack in the place of a Community. We believe that this dislodgement is a liberating movement, albeit one that also brings new disconcerting ethical questions.

In “Against the Romance of Community”, Miranda Joseph warn us of how this concept, so precious for leftist identity movements, is an extremely romanticized one, for the left and the right alike. And that it can also be used by neoliberal and even fascist discourses, such as communitarian nationalism. One of the ideas deeply embedded in the Community concept, and the one that opens its usage for fascist discourses, is that it is based on a binarism of “us/them”: who is inside the community/who is not part of it. A fixed enemy is always needed. As written by Chantal Mouffe: “To construct a ‘we’ it must be distinguished from the ‘them’ and that means establishing a frontier, defining an enemy” (Mouffe, 1993, p.234). The author also reminds us that “an organic unity can never be attained, and there is a heavy price to be paid for such an impossible vision” (Mouffe, 1993, p.5). We must taint this ideal of purity. In the general precarity state of our contemporary society, we should try to think of alliances as fleeting acts. We are not looking for Faustian bargains, but maybe for a sense of “cruising,” in the same queer vein that José Esteban Muñoz proposes in “Cruising Utopia.” Could we think of promiscuity as an ethical act? Engaging with different discourses in the moments that they would bring a positive outcome, and then shifting to others that can suit us better in a new moment. We should recall and conjure the “incostância da alma selvagem” [inconstancy of the Indigenous Soul], as called by Viveiros de Castro. An inconstancy that haunted the Portuguese Jesuit priest Antônio Vieira, since one could never truly know if the Catholic teachings were being accepted by the native Brazilians: one moment they seemed to listen to the sermons, the next they would do the exactly the opposite of the things they had just agreed with. “Nunca fomos catequizados. Fizemos foi o Carnaval.” (Andrade, 1928). Could we use this inconstancy and the perpetual movement it evokes, as a way of proposing new alliances? We know that this chaotic movement can also risk itself in perpetuating ambivalent ideas and/or imaginaries, such as the brown face in Book of Jessica. But, as written by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in her wonderful book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, this “contaminated diversity (…) is complicated, often ugly, and humbling” (Tsing, 2015, p.33). But it is in this cacophony that we must try to find ways of collaboration, denying the image of self-contained individuals. We should promote infections. Marx counsels us to let the dead bury their dead, but what would happen if we conjured them in a profane necromancy? If they imposed this colonial wound, we should spread it in their flesh, as zombies. “Everyone carries a history of contamination; purity is not an option” (Tsing, 2015, p.27). We, the pack, hate purity. We want to sniff mushrooms with its interconnected roots, we want to help propagate the contamination of its dispersing spores.

More precisely, commenting, if it means thinking-with, that is becoming-with, is in itself a way of relaying . . . But knowing that what you take has been held out entails a particular thinking “between.” It does not demand fidelity, still less fealty, rather a particular kind of loyalty, the answer to the trust of the held out hand. Even if this trust is not in “you” but in “creative uncertainty,” even if the consequences and meaning of what has been done, thought or written, do not belong to you anymore than they belonged to to the one you take the relay from, one way or another the relay is now in your hands, together with the demand that you do not proceed with “mechanical confidence.” [In cat’s cradling, at least] two pairs of hands are needed, and in each successive step, one is “passive,” offering the result of its previous operation, a string entanglement, for the other to operate, only to become active again at the next step, when the other presents the new entanglement. But it can also be said that each time the “passive” pair is the one that holds, and is held by the entanglement, only to “let it go” when the other one takes the relay. (Stengers apud Haraway, 2016, p.134)

It is important to notice that none of these authors propose us to abandon the idea of community as a whole, but urge us to think “for the inevitable implication of community in capital, for the simultaneous support and displacement that community offers to capital, for the complexity and instability of that relation as a dialectic of complicity and resistance—recognize the implication of our communities in the very forces we seek to oppose” (Joseph, 2002, p.xxv). I (we?) believe that this implication is strongly noticeable in how some concepts originated by queer and feminist movements were so easily appropriated by neoliberal discourse, such as empowerment or representation. Even if we admit that Capitalism is an always-moving force that attempts to appropriate almost everything, could we dare to propose that the “perpetual motion” evoked by the schizo dream, The Divisor and Simone Forti’s Huddle could be seen as a possible strategy to mislead this hungry beast, at least for some time? Capital is also in a perpetual motion, so one should not expect to find a decisive and perpetual way of avoiding it. We need to find other ways of being-with, one that is open to changes and to the risk of contingency, and one that is formed “through coalition—affinity, not identity” (Haraway, 1991, p.155). Like the nomad tribes from Kafka’s “The Great Wall of China,” we must move “with incredible agility, like locusts” (Kafka, 1946, p.84) , and be always prepared to pull down the blocks of a wall supposedly constructed for our protection, but that is based on the idea of rigid divisions. We, the pack, abhor walls. We want to destroy walls to pieces and then move the debris to confound everyone, including ourselves.

These blocks of wall left standing in deserted regions cold be easily pulled down again and again by the nomads, especially as these tribes, rendered apprehensive by the building operation, kept changing their encampments with incredible rapidity, like locusts, and so perhaps had a better general view of the progress of the wall than we, the builders” (Kafka, 1946, p.84)

We are not proposing the pack as an exhaustive concept, neither as one that should completely substitute the idea of community. We present it as just one possible way of trying to find and create other discourses and possibilities of “being-with,” especially trying to dislocate it from a vocabulary that relates only to Humans. It is known that a lot of different Objects in the world (the Human being just one of those Objects) also work as connected entities. “Biological studies in quorum sensing discovered that bacteria – among the oldest known life forms – do not function as a singular organism but communicate, coordinate, and adapt to their environment. The realization that animals, trees, the earth, and all else have agency that exceeds human comprehension has now made it into popular culture” states Diana Taylor in ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming). Forming alliances for survival is far from being indicative of Man’s superiority over other species. It is important to notice that we are not proposing an idyllic view of interconnectedness as another fancy way of celebrating the “amazing melting pot” of differences. We are not trying to propose a holistic version of being-with, as the one seen in James Cameron’s blockbuster Avatar. There will always be the unknown, the one that refuses to unite, the one that proposes other directions, the one that wants to be still instead of dancing or walking. If we try to preach this new holistic version of interconnectedness, would we not befall the same violent fate in which we are now? Maybe the idea of a linear time and of a progressive narrative, in which almost all of us are embedded, urges us to think of strategies that would last “forever”: the eternal peace, the eternal communion, the eternal revolution. But there are other ways of thinking temporalities, and maybe we could just try to find little breaches in where we can create these fragile alliances. Always movement. And in these brief moments, I hope we can meet each other, be with each other for a dance, for a party, for a protest, for a march. And after that, who knows? This contingency might not be the most comfortable position to be in, but maybe it is the one that we can propose.

Lepecki, André. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. New York and London: Routledge, 2006. Print.Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Cannibal Metaphysics: For Post-Structural Anthropology. Trans. Peter Skafish. Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing, 2014. Print.Johnson, Barbara. "Using People: Kant with Winnicott" The Barbara Johnson Reader: The Surprise of Otherness. eds. Melissa Feuerstein, and Bill Johnson González. Lili Porten, Keja Valens, 262-274. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. Taylor, Diana. "We Have Always Been Queer" ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence. 1-31. Durham: Duke University Press, Vazquez, Alexandra T.. "You Can Bring All Your Friends." Small Axe 20. no. 1: 2016. Accessed 16 Nov 2018. Campbell, Maria. Half-Breed. Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1983. Schechner, Richard. Between Theatre and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985. Taylor, Diana. ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. Noland, Carrie. Agency and Embodiment. Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press, 2009. Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A thousand plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. Print.Anzaldúa, Gloria. Boderlands: La Frontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Book Company, 1987. Print.Kaprow, Allan. Essays On the Blurring of Art and Life. ed. Jeff Kelley. London: University of California Press, 1996. Griffiths, Linda, and Maria Campbell. The Book of Jessica: A Theatrical Transformation. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 1989. de Sousa Santos, Boaventura. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, 2014. Quijano, Aníbal. "Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y Amércia Latina" La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales, 2000. 201-246. Print.Quijano, Aníbal. "Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America" Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate. 181-222. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2008. Mbembe, Achille. "Necropolitics." Public Culture 15. no. 1: 2003. Accessed 29 Sep 2018. Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1969."In a pack there is also no homogeneity: the pack is nomadic, it is always moving both in a geographical sense and in its own structure. Its hierarchies can always be changed: the leader is not in a definitive position, but is always gambling this leadership, which is open for others to take. It is not necessarily always peaceful among its members, since they can fight among themselves, or even create other packs. There is always movement, always the risk of failure."

Rancière, Jacques. "A estética como política." DEVIRES 7. no. 2: 2010. 14-36."A commitment that she has to reaffirm every morning when she chooses to lend her body as an enunciation site, defying the State’s necropolitics by transforming herself into a channel and an antenna that amplifies the sound of Marielle’s death and its implications to the citizen’s common life. That is what makes an ethical alliance possible."

"... the colonial wound enacts the biopolitics of life, the violence that accompanied imperialist expansions and outlasted till the present, exposing the unsaturated fractures of the nation’s political body."

-Susana Costa Amaral

"The work of achieving a synthesis may never be complete (not everyone can move in the same way or at the same pace), but it is in the habitually and collectively renewed decision to keep going... [that] enacts a pact.

-Annie Seminara

"The work of achieving a synthesis may never be complete (not everyone can move in the same way or at the same pace), but it is in the habitually and collectively renewed decision to keep going... [that] enacts a pact.

-Annie Seminara

Harrison, Marguerite Itamar. "Envisioning the Body Politic through Dense Layers of Paint: The Art of Adriana Varejão." Chasqui: Revista de literatura latinoamericana 37. no. 1: 66-78. Munanga, Kabengele. Rediscutindo a mestiçagem no Brasil: Identidade nacional versus identidade negra. Petrópolis - RJ: Vozes, 1999. Bhabba, Homi K.. 1895. "Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree outside Delhi, May 1817." "Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree outside Delhi, May 1817." Critical Inquiry 12. no. 1: 144-165. Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015. Print.Butler, Judith. "Giving an Account of Oneself." Diacritics 31. no. 4: 2001. Accessed Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2010. Pode o subalterno falar?. Belo Horizonte: Editora da UFMG, da Silva, Denise Ferreira. 2007. Toward a Global Idea of Race. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Butler, Judith, and Athena Athanasiou. "Preface" Dispossession: the performative in the political. ix. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013. Mbembe, Achille. "Postcolonial Thought Explained to the French: An Interview with Achille Mbembe." Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism 1. no. 1: Accessed 22 Nov 2018. Kafka, Franz. The great wall of China and other stories. New York: Schocken Books, 1946. Print.Haraway, Donna. Staying with the trouble. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016. Print.Césaire, Aimé. "From Discourse on Colonialism" Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader. eds. Patrick Williams, and Laura Chrisman. 172-180. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.